Update

More than a structure: Construction projects build community

Mar 4th, 2022

Every purchase has an economic, environmental, cultural, and social impact. Social procurement is the intentional effort to leverage social value outcomes from existing purchasing.

Procurement is shifting so that organizations no longer decide what to buy or who to contract with simply based on the lowest price. When we use social procurement to purchase goods, services, or choose a construction contractor, we’re deliberately balancing the environmental impact, the social value outcomes, the product or service requirements, and the price.

Over the past decade we have witnessed the emergence of social procurement policies and initiatives across numerous entities as they adjust their historic purchasing criteria from lowest price to best value. Leveraging a social value from existing buying offers an opportunity to solve persistent and complex social and environmental issues.

Recognizing the strength of their purchasing power, government has become an early leader in the adoption of social procurement initiatives.

“As the largest public buyer of goods and services, the Government of Canada can use its purchasing power for the greater good. We are using our purchasing power to contribute to socio-economic benefits for Canadians, increase competition in our procurements and foster innovation in Canada.”

Public Service and Procurement Canada [1]

The size and breadth of governments’ purchasing power includes billions of dollars spent every year on construction projects and infrastructure investments. From repairing a school, building a new fire house, a road replacement, or a new bridge, each project requires labour and purchasing of a multitude of goods and services.

Across all levels of government in several countries, including Canada, USA, Scotland, Sweden, UK, and Australia, policy is being designed and implemented to leverage existing purchasing or to use community benefit agreements to achieve social value outcomes that build community capital.

Healthy communities are built when procurement becomes more than merely an economic transaction. Through social procurement, the purchasing process becomes a transformative tool. With social procurement embedded into the process, construction is about more than the structure, construction projects build community.

Social Value Marketplace: Demand & Supply

The purpose of social procurement and community benefit models is to leverage the demand side of the construction industry market to achieve added social value. As we see increased demand for social value from suppliers, more social value is created.

This shift towards social procurement and community benefits in construction is a clear path to achieving multiple social value goals. From ending poverty to impacting climate change, the construction industry holds the capacity and opportunity to influence these outcomes.

Social Value Suppliers: Mike’s Story

Mike,[2] a Red Seal Carpenter with 7 years of experience, was injured on the job – setting off a chain of events that would change his life. The injury recovery required pain medication. This prescription led to a drug dependency, which led to addiction, which led to Mike losing his health, his job and benefits, and required a tough three-year struggle through recovery.

Now, Mike faced a new battle: to rejoin the workforce. With resume in hand, but a three-year gap in work, potential employers questioned his ability to re-enter the labour market, keeping him unemployed and causing Mike to have increasing self-doubt. A friend recommended he check out EMBERS Staffing Solutions, a social enterprise that hires day labour staff for the construction industry. Mike, with work boots, hard hat and tools from the EMBERS library, was on a job site the next day.

Once on the job, Mike was able to demonstrate his skills and commitment. Within three months the General Contractor on the project, seeing his skills and commitment, offered him a full-time permanent position.

EMBERS is a social enterprise operated by a charitable organization based in the infamous Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, one of Canada’s poorest postal codes and home to thousands of struggling residents. On any given day, EMBERS’ Staffing Solutions will have over 400 people facing barriers to employment working as temporary labour throughout the area’s construction projects. Over 50% of these workers will move on to working full time in the construction sector, earning a living wage, and becoming a healthy member of the community. Work opportunities for each of these employees, like Mike, means a chance to exit poverty, build a skill, find friendship, feed their family, and more.

Mike’s journey is not uncommon. But without social procurement, his successes may not have occurred. EMBERS was able to provide this opportunity to him, and many others, because the General Contractor was meeting social procurement requirements on site. To meet social value targets to support hiring persons facing barriers to employment, the GC had contracted EMBERS to provide day labour.

Construction companies can choose from many temporary labour services, but only EMBERS, a competitor in this market area, offers a full program of employee supports, including training, insurance, good wages, and even encouragement for their workers to move on to full-time permanent work through collaborative programs with their business clients.

Mike’s story contributes to the fact that EMBERS’ collective activities achieve at least a dozen of the UN SDG’s every day. Imagine this story amplified across the globe!

There are other effective construction social enterprises across Canada seeking to create healthy communities and support people through employment. BUILD, a social enterprise in Winnipeg, MB, trains and employs youth at risk in the building trades. Build Up Saskatoon offers steady employment, mentorship, and other social supports to employees to aid them towards meaningful, long-term employment in the construction industry. Building Up in Toronto works with persons facing barriers to enter the labour market through jobs in the construction industry. Impact Construction in St. John’s, NL, has built their business model to support youth to gain skills and a successful future.

Social enterprises provide other services to the construction industry supply chain as well, including trailer cleaning, junk removal, printing and signage, catering and food trucks, security, couriers, and much more.

As most sites have multiple sub-contractors and trades on the job, providing jobs, creating training and apprenticeships, and using social value suppliers is not just the role of the primary contractor. To amplify social impact, look across all the opportunities available onsite.

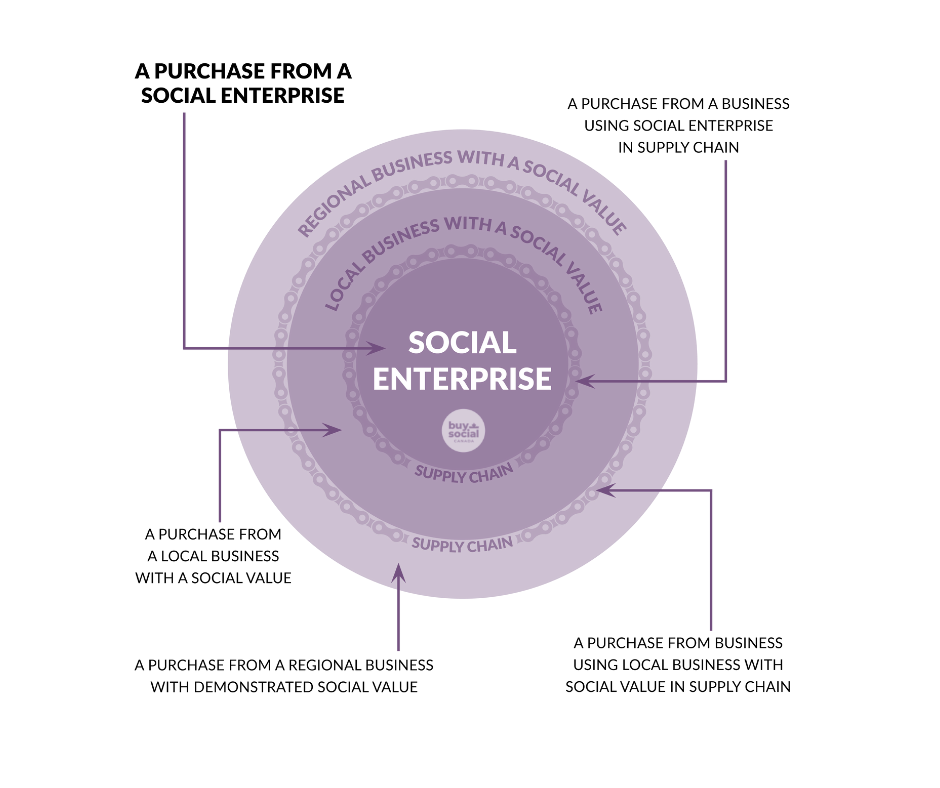

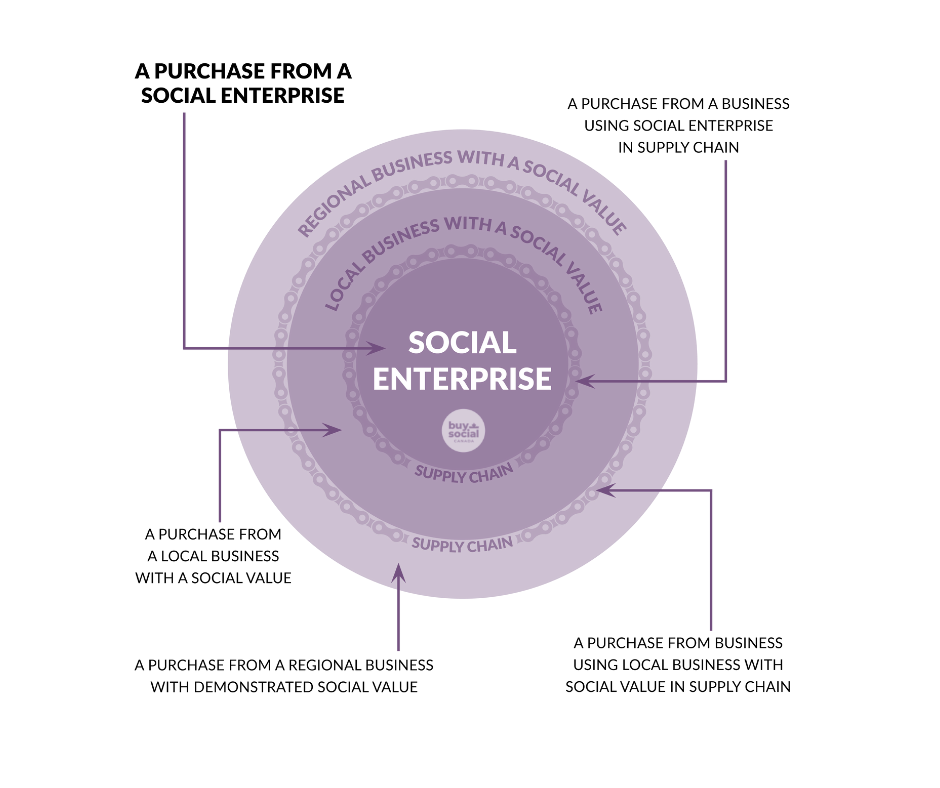

If a social enterprise isn’t available, then use the concentric circle model to look for other social value suppliers; depending on your goals this could be an Indigenous, Black, or women-owned businesses, a co-operative, a B Corporation, or a local business.

Value For the Construction Sector

Internationally there is a growing labour shortage in the skilled trades. With over 40% of the current employees set to retire in the next 15 years, the problem is nearing catastrophe. The sector has a labour need, and the community has an employment gap for youth, recent immigrants, and equity-deserving community members.

Chandos Construction, an employee-owned, B Corp-Certified general contractor and a Buy Social Pledge Founder, is a leading example of how to leverage their role as both supplier and purchaser to lead the construction industry in implementation of social procurement and achieving SDGs.

As a social purpose business who is committed to achieving net zero by 2040, Chandos increases their competitive edge with owners and government buyers looking to meet social procurement targets, community agreement goals and environmental objectives. In their supply chain, they use their purchasing to enhance opportunities for diverse employment, and have a commitment that 5% of all controllable spend will go to social enterprises and diverse-owned businesses. For example, EMBERS is their preferred labour source when working in Vancouver. The result? Increase in contracting opportunities, more engaged employees, a stronger financial bottom line, and measurable community impact.

Other construction companies are also stepping up to create change through social procurement. Bird Construction, a Buy Social Engage Member, has partnered with Chandos to support the Building Good initiative, with the goal to innovate the construction sector for increased social impact. Clark Builders, a Buy Social Pledge Member, has made a commitment to social procurement in their organization and supply chain.

Can we use social procurement to address this gap?

Governments at all levels and in multiple countries see their opportunity, and the need, to leverage social value outcomes to meet their social goals of equity, social inclusion, poverty, climate change, and more, which all align with the UN SDGs.

Government policy is increasingly requiring proponents to create social value from existing construction projects. But some early perspectives see the emerging policies as extortion for social value, a distraction, or merely an added cost. The evidence of best value through procurement is still a nascent movement, with a need to address pre-existing perceptions through research and case study evidence.

Dr. Daniela Troje, through interviewing key actors in the Swedish construction sector and reviewing policy-in-practice literature, concludes that while social procurement policies can mitigate issues connected to social exclusion, unemployment and segregation, the construction sector holds opportunities to be an appropriate sector for social procurement. There is currently a misalignment between social procurement policies.[3]

From the other end of the globe:

“There has been a recent proliferation of social procurement policies in Australia that target the construction industry. This is mirrored in many other countries, and the research in this area shows that these policies are being implemented by an emerging group of largely undefined professionals who are often forced to create their own roles in institutional vacuums with little guidance.”[4]

What often begins with resistance and strictly as a matter of compliance, can lead to a change in relationships between market segments. This is currently the case developing in social procurement and community benefit agreements across the construction sector: from fear and myth building to engagement, pilots and early successes.

When compliance becomes a market advantage in meeting social value requirements built into RFx and contract deliverables, the industry adapts. Initially, green building requirements were resisted from all sides of the sector; they were seen as too complex, too costly, without enough supply. Now, the industry competes to be the most green. Environmental leadership is a market advantage.

Social value outcomes are seeing a similar trajectory, moving from compliance to early adopters, to market requirement, to market advantage. Continuing this momentum will mean greater integration of social value suppliers and related outcomes in every construction and infrastructure project.

The Future

As we move the story from a few people like Mike to a multitude of evidenced research results, we will create community capital with each new targeted job created, with every apprenticeship for a person facing barriers to employment, and with every contract with a social enterprise in the supply chain. Construction does build community!

[1] https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/app-acq/ma-bb/posacfi-asgicfi-eng.html

[2] This story about Mike is a representation of the impact EMBERS has had with many individuals.

[3] Troje, D (2021) Policy in Practice: Social Procurement Policies in the Swedish Construction Sector, Sustainability

[4] Organisational legitimacy and support. Loosemore, M.; Keast, R.; Barraket, J.; Denny-Smith, G. “Champions of Social Procurement in the Australian Construction Industry: Evolving Roles and Motivations.” Buildings 2021, 11, 64